The New York Times. Orbituary.

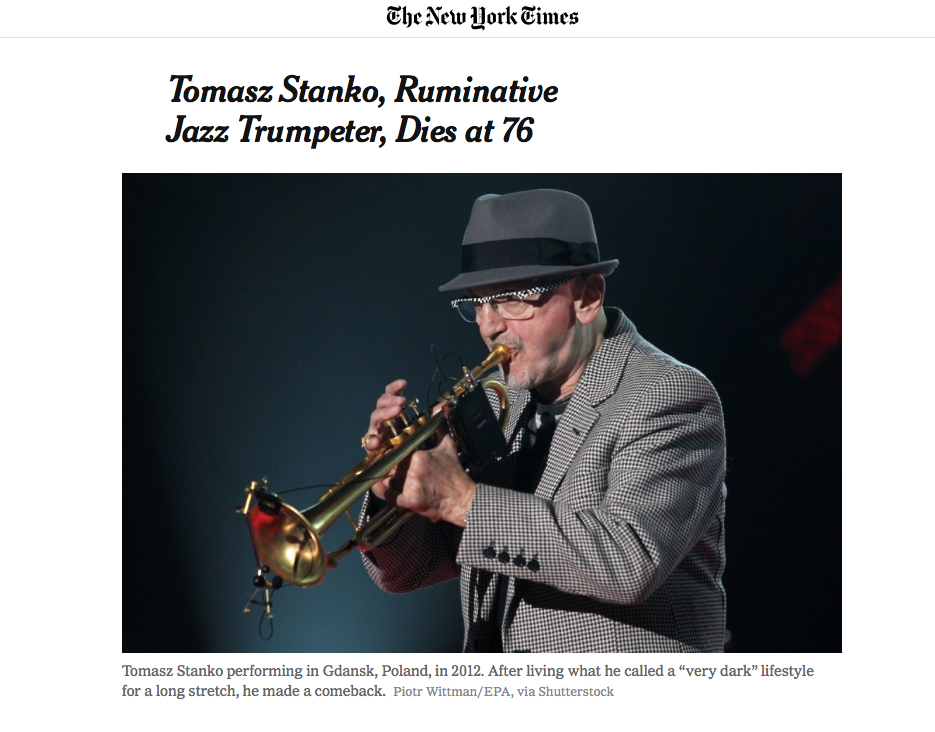

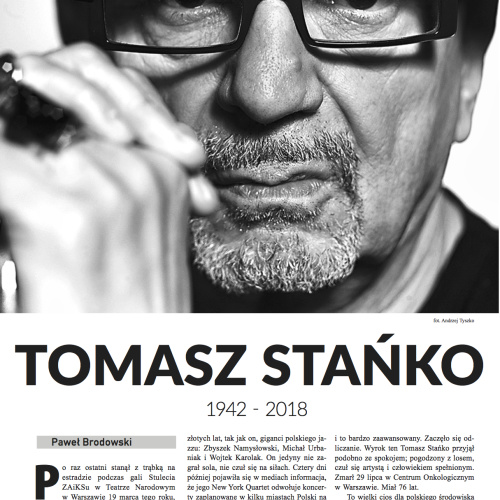

Tomasz Stanko, Ruminative Jazz Trumpeter, Dies at 76

Aug. 5, 2018

His daughter, Ania Stanko, said the cause was complications of lung cancer.

Starting in the early 1960s, Mr. Stanko’s even-toned, languorous trumpet playing endeared him to experimental musicians on both sides of the Atlantic. Over the years he played in ensembles led by Cecil Taylor, Gary Peacock and the influential Polish pianist Krzysztof Komeda.

But it was not until the 1990s that he emerged as a bandleader of international renown. From 1994 through last year, he released 10 albums on the distinguished German record label ECM, a run that forms a significant chapter in the history of modern-day jazz.

Mr. Stanko was one of the select few non-Americans whose music was included in the 111-track collection “Jazz: The Smithsonian Anthology,” released in 2011. His “Suspended Variation VIII,” from the 2004 disc “Night Variations,” was the final piece included.

In Poland, he was widely considered the country’s leading jazz musician, and he received accolades throughout Europe.

On his ECM recordings, Mr. Stanko used ensembles that usually featured top young musicians from across Europe or, in later years, New York City. Whether playing spacious group improvisations or pressurized music with a rugged pulse, he maintained a dark, melancholic air.

While his aesthetic remained steady, if flexible, his enthusiasms ran broadly. In his music, he professed to draw inspiration from Italian neorealist cinema, the poetry of Wislawa Szymborska, William Faulkner’s novels and the paintings of Amedeo Modigliani.

His 2009 album, “Dark Eyes,” was inspired by an Oskar Kokoschka painting, “The Dark Eyes of Martha Hirsch,” which Mr. Stanko came across at the Neue Gallery in Manhattan.

The year before, he had realized a lifelong dream when he moved to New York.

“Of course, I am not a New Yorker,” he told the New York public television station Thirteen. “I am only living partly in New York. But I have a small apartment on the Upper West Side, and I feel fantastic that I can enjoy the city every morning, the style of life, the energy on the street.”

Tomasz Stanko was born on July 11, 1942, in Rzeszów, a city in southeastern Poland, which was under German occupation at the time. His mother, Eleonora, was a teacher. His father, Josef, was a judge and sometime violinist who encouraged Tomasz to pursue music. At first he studied classical piano and violin.

As a youth in Communist-ruled Poland, Mr. Stanko was exposed to jazz through Willis Conover’s broadcasts on Voice of America radio. He first heard live jazz in 1956: a concert by the Dave Brubeck Quartet in Kraków, where Mr. Stanko was studying.

“The message was freedom,” Mr. Stanko told The New York Times in 2006, recalling that first exposure. “Jazz was a synonym of Western culture, of freedom, of this different style of life.”

But the musicians he originally fell in love with, the trumpeters Miles Davis and Chet Baker, were not boisterous players. Their version of freedom, he found, had an existential bent, a brooding autonomy, that resonated with him. He eventually quit his classical studies and took up the jazz trumpet.

By 18 he was playing professionally, and in the early 1960s he formed partnerships with two pianists renowned in Poland, Adam Makowicz and Mr. Komeda. Mr. Stanko was featured on Mr. Komeda’s 1965 quintet album, “Astigmatic.”

Clearly influenced by Ornette Coleman and Don Cheery, that record had the sultry mystery and bristling angularity of early American free jazz, but it also hinted at the dark, spacious architecture that would define much of Mr. Stanko’s career.

“I felt that if I want to be a really good musician, I want to be serious with this art, I have to build my own language,” he said.

He was soon leading his own ensembles. In 1970, a state-owned record label, Polskie Nagrania Muza, released his debut album, “Music for K,” in which he fronted a quintet that played lacerating, tumbling improvisations.

He made his ECM debut five years later, recording the arresting album “Balladyna” with a quartet featuring the bassist Dave Holland.

Mr. Stanko would not record for the label again for nearly two decades. In the intervening years, he lived what he would describe as a “very dark” lifestyle involving substance abuse; in the early 1990s his teeth began falling out.

That would have marked the end of many trumpeters’ playing careers. But Mr. Stanko, on his way to recovery, took it as a challenge, spending months practicing in front of the television, learning to play with false teeth and restoring his old sound.

He also changed his personal habits. “I stopped using dope, I stopped smoking cigarettes,” he said. “That was kind of fantastic.”

Signing again with ECM, he released the critically lauded album “Matka Joanna” in 1994, then followed it with a string of other standout albums, many made with the Swedish pianist Bobo Stenson. He also recorded for other labels, making forays into synthesizer-laden jazz fusion, such as the 2005 album “Freedom in August,” and the more successful “Chameleon,”from 2006.

Mr. Stanko also composed for films and theater, and in 2014 his “Polin,” a suite dedicated to the memory of Polish Jews who died in the Holocaust, had its premiere. In 2010 he published an autobiography, “Desperado,” in Polish.

In addition to his daughter, Ania, who was his manager, Mr. Stanko, who died in a hospital, is survived by a sister, Jaga Stanko Ekelund. His marriage to Joanna Stanko ended in divorce.

Correction:

An earlier version of this obituary referred incorrectly to the bassist Dave Holland, who was featured on Mr. Stanko’s album “Balladyna.” He was not a key associate of the musicians Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry.