Tomasz NYQ, London Jazz Festival 2017

ECM documented the first breakthroughs of European jazz freethinkers, including saxophonist Jan Garbarek, bassist/composer Eberhard Weber, and the late Finnish maverick Edward Vesala – and Stanko, too, a star from the label’s early years; likewise John Surman, a former west country choirboy transfixed as a teenager by John Coltrane. Surman was with composer John Warren in a festival one-off at Kings Place on Sunday with a tight brass section and their original bass and drums partners Chris Laurence and John Marshall to revisit Warren’s sumptuous and swinging Traveller’s Tales suite, the only other public performance of which had been on the debut of the festival. That subtle music, and its main practitioners, didn’t seem to have aged a bit.

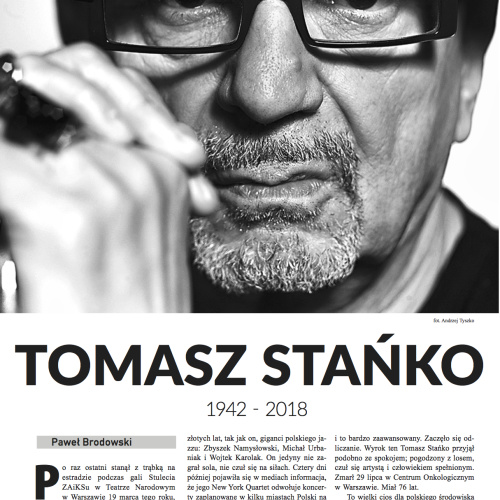

On the festival’s opening night, Stanko’s brilliant band showed how creatively old Europe and new America could be fused in the cauldron of jazz. “The mood of Polish melancholy is in my blood,” Stanko once said – always mistily evident in his gruffly sonorous trumpet sound and his frequently twilit, cautiously unfolding themes. But, if that background shaped the concert’s eerie ghost dance of December Avenue, or the desolate long tones of Ballad for Bruno Schulz, American jazz danced with it – in Stanko’s fiery, precisely grooving improvisations, in three blistering solos of fast postbop and blurs of percussive chording from the Cuban/American David Virelles, and in the intensity of his American rhythm team of bassist Reuben Rogers and drummer Gerald Cleaver.

A complete European jazz contrast was furnished the following night by Out of Land, a scintillating new quartet with multiple virtuosic limbs and one irrepressibly surreal mind. French soprano saxophonist Emile Parisienembarked on every solo as if playing for his life – spindly legs waving in the air in fascinating synchronicity with his phrasing, and accordionist Vincent Peirani, playing in bare feet, was by turns rapturous and stomping. Swiss vocal phenomenon Andreas Schaerer merged falsetto choral purity, African click sounds, and jabbering scat, while pianist Wollny threaded a lyricism drawn from classical music and jazz through the headlong proceedings.

The quartet’s chemistry was of free jazz, accordion romancing and avant-classical vocal gymnastics that owed as much to a five-decade tradition of European free-improv, to French chanson and contemporary-classical experimentation as it does the jazz tradition, and it was a synthesis hard to imagine from even the most left-field US band. But it couldn’t have happened without jazz coming first – and in an era in which America can struggle to feel proud of its foreign interventions, maybe that means a lot.